By Nora Comstock

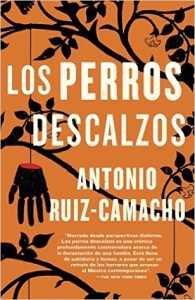

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho was born and raised in Toluca, Mexico. A former Knight Journalism fellow at Stanford University, a Dobie Paisano fellow in fiction by the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas Institute of Letters, and a Walter E. Dakin fellow in fiction at Sewanee Writers’ Conference, he earned his MFA from The New Writers Project at UT Austin. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, Texas Monthly, The Millions, and elsewhere. His debut story collection Barefoot Dogs won the Jesse H. Jones Award for Best Book of Fiction and was named a Best Book of 2015 by Kirkus Reviews, San Francisco Chronicle, Texas Observer and PRI’s The World. It was published in Spanish translation by the author, and is forthcoming in Dutch. Antonio lives in Austin, Texas, with his family, where he’s currently at work on a novel.

Nora Comstock

How did the idea of this, your first book, come about? Was it something you planned or did it surface out of your journalism as a stories or experiences that begged to be told?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

It was unplanned and unexpected. I wrote most of the stories in the book while at my MFA at UT. Around that time —between 2010 and 2012 – the wave of violence in Mexico reached its peak. Hundreds of thousands of Mexican citizens were displaced as a result of the drug war, and many of them, across all social and economic backgrounds, sought refuge on this side of the border, leaving everything they had behind overnight. I grew haunted by the wave of disappearances, kidnappings and extortion ravaging the country where I was born and raised and where I lived until I was 28, but I was experiencing all of it from afar, while already living in Austin. I guess my way to process my sense of helplessness and indignation about it was to channel it in my fiction.

Nora Comstock

As the idea evolved, was there ever a time you thought of it as a novel instead of related short stories?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

No, never. I liked the idea of this being a series of linked stories, and that the threads that weave them together are sometimes evident, while other times barely noticeable. I never considered the possibility of turning this narrative into a novel. I don’t share the vision that turning a story collection into a novel is in any way an improvement or an upgrade, or that you are a better writer for writing a novel instead of short stories–that you may “graduate” from the short form once you get to write something longer. Both forms are incredibly wonderful and hard to write, but this every writer knows–the shorter the piece, the higher the stakes.

Nora Comstock

In what ways does your personal experience inform the stories?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

In the same way that any other fiction writer may write about the themes that obsess them. Over time I’ve realized I mostly write about things I’ve lost. There’s a lot of loss and nostalgia in my fiction, which is ironic because I’m one of those people who think, foolishly perhaps, that the best of everything is yet to come.

Nora Comstock

Did the stories change much from the initial writing? In what way?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

Some of them did, like “Origami Prunes” or “I Clench My Hands…”, but others didn’t. The final version of “Better Latitude” is incredibly close to the first draft I wrote.

Nora Comstock

What is the significance of the title?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

It’s right there in the last story of the book, for every reader to make sense of it.

Nora Comstock

Did you have to do research to fill in any of the stories?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

Most of my research usually has to do with geography, especially when I’m writing about places I no longer inhabit, like Mexico City, Madrid, or Palo Alto. I guess it’s a professional deformation coming from a journalistic background. I need to get the places where my stories take place right, even if later on in the process I will completely deform them or do weird things to them. For all the nefarious things the internet has brought about, Google Maps is a thing of beauty.

Nora Comstock

How long did it take you to write this book? Which was the most difficult story to write? Why?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

I wrote the first draft of the first story I wrote from the book around September, 2010. I completed the final version of the last story I wrote around March, 2014. The hardest one to write was “Origami Prunes,” or “the laundromat story,” as some readers call it. A lot of weird things happen in that story in terms of time, setting, character, voice. I struggled a lot finding the right ending to the story.

Nora Comstock

Do you have a favorite story or one that has stayed with you longer than others?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

“Origami Prunes,” for the same reason. I’m very proud of that story because it is outrageous and corny and devastating and unnerving and funny, all at the same time, and when I meet a reader who tells me it’s her favorite story from the book, it always makes me go all high-fives.

Nora Comstock

The characters in each story sketch the landscape of shock, fear, confusion, desperation, isolation, and loneliness of various family members, youth and adult, and maids who have to try to make sense of the a future that is nothing like the past. And the mistress must come to terms with explaining to her child, the story of his father. Did the characters come from your journalistic experience in covering stories in Mexico and other countries or did you create them to serve a specific purpose?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

The characters come to me in the form of visitations and stick around in my mind, haunting me, until I finally give in and sit down and start writing their stories. They come as they are, I’m not responsible for their personality or background or behavior. They don’t serve a specific purpose other than, hopefully, being memorable, or at least stubborn enough to harass me until I write about them. I’ve met people exactly like them in real life in many different contexts, both professional and personal ones, both in Mexico and elsewhere.

Nora Comstock

Did you have other stories that did not make it into the book or were these stories specifically crafted to illuminate an aspect of the situation?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

These were all the characters that came forward to share their stories with me. There’s a family tree at the end of the book that features other family members—domestic workers included—who do not appear in any of the stories. I sometimes wonder about them–how did the disappearance of the patriarch affected them or shaped their lives moving forward? It’d be nice to know.

Nora Comstock

How did you decide the order of the stories? Which was written first, last?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

I wanted to give the collection a tenuous sense of narrative arc, and I wanted to use the patriarch as a leitmotiv for the whole book. I realized readers would wonder about him–what happened to him in the end, who he was, how he came to shape his family and the people who worked for them. That was the driving force before the order of the stories in the book.

The first one I wrote was “Deers.” The last one, “Her Odor First.”

Nora Comstock

You were born in Mexico, when did you learn to read/write English? When did you feel comfortable expressing yourself in English?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

As any other Mexican middle-class kid, I attended bilingual private schools since I was in kindergarten, but only when I moved to the US in 2004 did I realize I was not nearly as fluent in English as I thought I was. I still don’t feel comfortable writing in English–I never will. What happened was that I fell in love with the language, its flexibility, its generosity, its playfulness. Each language is a particular way to see the world and engage with it, and I fell in love with the way I engage in English with the world that haunts me. Also, I love challenging myself, and the challenge of writing in a language that I’m constantly thinking will end up defeating me is intoxicating. I’ve embraced that challenge and that sense of discomfort.

Nora Comstock

Why did you choose to write this book in English instead of translating it from Spanish?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

It was not an option. I began to write in English out of necessity. Back in 2008, I got a Knight Fellowship for journalists at Stanford. By then, I had been working on a novel–in Spanish–intermittently for almost nine years. When I finished it–or I thought it was finished–I began to submit it to contests, editors and agents in both Mexico and Spain, but nothing ever happened–I wouldn’t even get rejection letters. I realized I had to improve my writing, and decided to take creative writing classes at Stanford. The problem was, there were no classes in Spanish–the only options available were in English. I decided I’d take these classes anyway, hoping that they would help me improve my writing somehow, but I never once considered at the time I would end up writing in English beyond Stanford–let alone publishing a book. To my surprise, the feedback I received from the very beginning was very encouraging. By the time I left Stanford I’d decided to keep pursuing writing opportunities in English as long as these would make themselves available to me. Back in Austin I applied to MFA programs in Central Texas–regular MFA programs, all of them in English–and was admitted to UT’s The New Writers Project (UT Austin, and the English Department in particular, has been so supportive of my work–they believe in me more than sometimes I do myself). The rest, as the cliché goes, is history.

Nora Comstock

Today when you write, do you think in Spanish or English? The story named “Deers” brings learning a new language into focus as the Mexican maid who was fired found work in the fast food industry. She is trying to comprehend usages in English.

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

I think in English most of the time, but my Spanish is always working in the background. Whenever I can’t find the right word in English, I take to Spanish, find the right word and then translate it back into English. From then on I try to find the word that best conveys the meaning and musicality I’m aiming for–in English.

Nora Comstock

I understand you will be in charge of translation of the book into Spanish. Will you be doing it yourself? One of my colleagues whose first language is Spanish says she will not translate her own English work because she always ends up trying to re-writing the story to make it better. Your thoughts?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

The Spanish translation was published by Literatura Random House in Mexico in October, 2015, and by Vintage Español in the US in April, 2016. I was in charge of the translation. Before I started, I made a conscious decision that I would just try to convey the stories in Spanish as they were, without changes. The English edition is the original and definitive version of the book.

Nora Comstock

Do you have favorite writers whose works influence your own writing?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

The writers I first fell in love with, those I just naïvely wanted to emulate because I admired them so much, are, if you will, my biggest influences, even if such influence might not be clear or evident on my work. These are Javier Marías, Mario Vargas Llosa, Jorge Ibargüengoitia and José Emilio Pacheco. And Joan Didion. In The Year of Magical Thinking, she wrote: “I never actually learned the rules of grammar, relying instead only on what sounded right.” If I’m able to write a coherent sentence in English, it is because of her.

Nora Comstock

What do you want people to take away from reading this book?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

I want them to have a good time reading it. My hope is that these stories make them feel something – what, I don’t know, I don’t care, as long as the book moves them in any way. My dream is to tell a story that makes the reader turn to the person next to her after she finishes and say, “You need to read this,” because that’s one of the biggest joys I experience as a reader myself. That’s my only agenda.

Nora Comstock

How was the book received in Mexico?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

The comments have been overall very positive. Most of them have to do with the family and class relationships depicted in the book. Those who have read the book in Mexico have told me that they relate to the characters, or that the book feels distinctively Chilango (the demonym for Mexico City residents), which is great.

Nora Comstock

Given the violence in Mexico today, there is talk about citizens arming themselves for protection or creating their own protection systems. They do not trust the current system to protect them. Is this a continuation of the situation and even an increase of the drug violence?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

The Mexican reality has always been much more complicated than what it looks like on the surface, or from afar. At any rate, I’m not an expert on the ongoing situation in Mexico – after all, I left the country in 2001. I’m happy if the book creates an opportunity to discuss our Southern neighbor in all its complexity and sophistication, especially given the agenda that the current US administration is pursuing. But I like to remind myself and my readers that this is a work of fiction, and that the kind of exploration about human nature that fiction can provide goes beyond its own geographical limitations.

Nora Comstock

What are you working on now?

Antonio Ruiz-Camacho

On a novel set in different parts of Mexico in the late nineties. The protagonists are a reporter, his late wife, who was a photojournalist herself, and the rise of a new violent, nihilist group inspired by religion–but not the religion you might be thinking about.

Dr. Nora Comstock is the Founder of Las Comadres Para Las Americas, Las

Comadres and Friends National Latino Book Club/Teleconference Series

and Count on Me: Tales of Sisterhoods and Fierce Friendships, the Las Comadres Para Las Americas compiled anthology. The National

Book Foundation awarded the book club the Innovations in Reading in

2014. Comstock was a partner in creating the Comadres/Compadres Writers Conference, which takes place in New York City at The New School. The first conference was held in 2012. In 2015 it introduced its first Writing Master Class. Comstock was recently been elected to a six-year term (unpaid) of the Austin Community College Board of Trustees.