By Syed Ali Haider

One of my favorite assessments of art is the Bechdel Test—a series of criteria that determine how successfully a work of fiction portrays its women characters. It has to have 1) at least two named women in it, who 2) talk to each other, about 3) something other than a man. If a work of fiction passes or not, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is good or bad. At least not in the sense that we normally talk about art. The importance of the test lies in what it says about the work of fiction’s perspective on the world—how it sees the world. The troubling thing about a story that fails the Bechdel Test is that, in its world, women are not prominent enough to exist in a world separate from men. If a woman does exist, her presence is only by virtue of her connection to a man.

I like the Bechdel Test. I think it is important. And I think art needs another, similar test. A Bechdel Test for non-white characters. To pass, a work of fiction must have 1) two named non-white characters, who 2) talk to each other, about 3) something besides a white character.

The United States is divided along cultural and racial lines. The loudest, most bellicose voice we’ve heard in modern politics now commands the most powerful country in the world, and he’s telling you that Muslims are dangerous. We’ve reached a point in our national narrative where the President of the United States is calling for a registry of and a ban on Muslims. Narrative matters, and Muslim stories are more important than ever. Vastly unrepresented in American fiction, the stories about Muslims we often hear come from the news. Stories featuring Muslims are more likely to be about terrorism than anything else. In a post-9/11, post-Trump America, Muslim narratives are scarce.

However, we’re seeing more and more of these stories emerge. HBO’s The Night Of told the story of a young Pakistani-American Muslim caught not only in the New York justice system but also in a maelstrom of anti-Muslim paranoia. He’s on trial for a number of things, but for the detective assigned to the case, Nasir’s Islam determines his narrative. We saw a similar narrative play out in the massively popular first season of the podcast Serial. In story after story, Muslims suffer and are interrogated because of their faith. But the power of these Muslim-dominated narratives is that they have the capacity to reshape the wider view of Islam in the world. Just like the art that passes the Bechdel test often gives you deeper, more nuanced women characters, these stories give us more complicated Muslim narratives than what Trump’s America imagines.

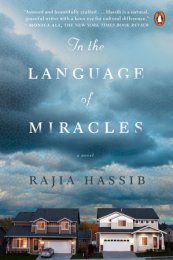

Rajia Hassib’s novel In the Language of Miracles passes the Bechdel test for non-white characters. It succeeds, however, in another way. The story demands that we pay attention to a Muslim-American family in grief. Although the narrative is not altogether new, it is one that is often unexplored from a Muslim-American perspective. It’s not just that they’re supporting characters, or that their lives exist only in opposition of a white person, but each of their narratives is fully fleshed out. The novel’s point of view roves from Samir and Nagla, the parents, to their youngest son, Khaled. With each of their stories, Hassib crafts unique Muslim narratives in reaction to a traumatic event. Much like Muslims after a terror attack, they are confronted, and by familial association, implicated.

The Al-Menshawys exist in a loop of fear and guilt that has become all too familiar for Muslims. In the wake of terror attacks, Muslims are regularly called on to denounce and apologize for their faith as though Islam and its 1.6 billion worldwide practitioners are a monolith. The Al-Menshawys’ eldest son, Hossam, murdered a neighborhood girl, Natalie Bradstreet. The family, in many ways, is held accountable and punished by the community. They are mistrusted and become targets of hate and online harassment. Unfortunately, this same narrative plays out for Muslims across the world. Hate crimes are on the rise. After the November 2015 Paris attacks, hate crimes against British Muslims rose 300%. The beauty of Hassib’s novel is that you’re brought into this family’s pain. You come to the other side and you’re forced to see the whites of their eyes. In a novel, monoliths come crashing down, and rich, varied stories are given their due.

With a memorial service for Natalie looming, the Al-Menshawys are noticeably not included. Early in the novel, Natalie’s mother visits the Al-Menshawys to explain that she no longer blames the parents, Samir and Nagla. Before long, her real reason for visiting surfaces. The memorial has become a public event. There are fliers all over town. While she’s not apologizing for the memorial, she quickly adds, “I do want you to know that this was not meant for you.” Samir takes her visit as an invitation. His wife disagrees:

“She was just being nice.” Nagla paused, raised one trembling hand to her forehead. “Because that’s how she is.”

Samir sat on the sofa, crossed his legs. “Twenty years in the U.S. and you still don’t understand Americans.”

The central tension of the novel begins here. Samir insists, against the will of his entire family, that they make an appearance, address the community and ask for amends. His wife, son, and daughter prefer a less conspicuous existence. They suggest relocating. Samir is stubborn. He stamps his feet. The family will go to the memorial, and they will go together dammit.

In the end, Samir subverts the Muslim narrative and confronts the world around him. He attends the memorial service with his reluctant family. In a world that demands from Muslims shame and condemnation, Samir holds his head up high. He chooses not to let his son’s crime dictate his present or future. He wants his community to know that he and his family are suffering.

When they finally exit their car, “[they] walked toward the heads now turned their way, against the outburst of whispers that exploded from the silence. Samir plowed through, his step slightly faster than usual, the increased speed recognizable only to those who knew him.” Rather than spoil the ending, I’ll instead focus on Samir’s audacity to be loudly and shamelessly Muslim. He pushes against expectation and decorum in order to grieve. He asks that in the wake of this horror, he and his family be allowed to have a space to exist. That they not have to shrink away and disappear.

Syed Ali Haider is the Program Director for Austin Bat Cave, a nonprofit that pairs teaching artists with underserved and marginalized student populations. His work has appeared in Glimmer Train, Juked, and Cimmaron Review. Roxane Gay selected his essay “Porkistan” for The Toast vertical, The Butter. He is working on a novel. You can follow him on Twitter at @SyedARHaider, but his Instagram is more fun.

Wonderful! The essay itself accomplishes the goals it defines–to create narratives that break the mold and to highlight the complexity and range of the Muslim story.

Also the writer looks handsome in that picture.

LikeLike

I don’t know about the book but your review is beautiful.

LikeLike